Harem an Arabic word meaning prohibited or the sacred enclosure. Harem, Harim or Herem was the secluded part of royal household where lived mothers, sisters, wives, daughters, entertainers, lady servants, concubines etc. Entry of outsiders into the Harem was prohibited.

अकबरनामा: Akbarnama (Set of 2 Volumes) (Rated 1.0) by शेख अबुल फजल (Shekh Abul Fazal) Look Inside the Book. Erasing Kashmir’s Hindu past. Islamization of placenames and attack on the Hindu past Today, international media, secularists and politicians from Kashmir are shouting from their rooftops that Kashmir is a Muslim Majority land and the abolition of Article 370 is a conspiracy to alter its Muslim Majority character.

The Harem system developed into a domestic institution under the Mughals. Abul Fazl in his ain-i-akbari and akbarnamah gives a vivid description of the Harem administration. The female apartment of the Mughal emperor was called Mahal. Abul Fazl named it as Shabistan-i-Khas. The ladies occupied a large portion of the royal household. They all had separate apartments. There were three more palaces in which the concubines of the emperor were accommodated. They were known as Leathevar (Sunday), Mongol (Tuesday) and Zenisher (Saturday) Mahals. On these days the emperor used to visit the said palaces. Besides these there was a separate palace known as Bengali Mahal for the foreign concubines of the emperor.

Akbarnama In English

The private rooms made for the Mughal queens were very rich. Acdsee photo studio ultimate 2020 license key. The ladies lived in splendour, pomp and luxury in these mahals where they sat and saw but could not be seen. Their enclosure contained splendid and beautiful apartments in keeping with rank and income. Every chamber had its reservoir of running water at the door, on every side were gardens, streams, fountains and comfortable resting places on which they could sleep coolly at night.

The emperors elaborately organised the harem. Chaste women were appointed as daroghas and superintendents of the harem and they were assigned different sections to look after. Matrons were appointed to maintain order and discipline in the harem. These ladies were given liberal salaries, which were disbursed by Tahvildars or the cash keepers. The highest female servant who controlled the harem was mahaldar. She also acted as a spy in the interest of the emperor or the king. The interference of the mahaldar often resulted in a quarrel between her and the princes of royal family because they did not relish the watchful eyes of these mahaldars.

The harem was guarded with great caution and attention. The most trustworthy women guards were placed near the apartment of the emperor. On the outer fringe eunuchs were placed and at a proper distance from them were deputed bands of faithful Rajput guards. No one could easily enter the harem. The doors of the harem were closed at sunset and torches were left burning. Each lady guard was obliged to send the reports to the nazir of all that happened in the harem. The written reports of all the events that occurred in the harem were sent to the emperor. Whenever the wives of some nobles desired to visit the harem, they had to notify first to the servants of the harem who would forward the request to the officers of the palace. After this, those eligible were permitted to enter the harem. Nazir was a term used for the eunuchs who guarded the harem. Each princess had a nazir in whom she reposed great confidence. Whenever the Emperor or the Nawab moved within the palace the procession was usually accompanied with kaneezes (women servants).

After the death of Mughal Emperor Shah Alam I in 1712, the central power in Delhi disintegrated through palace revolutions and independent provincial dynasties grew up in Bengal, Hyderabad and Lucknow. The independent Bengal nawabs maintained harem following the Mughal tradition. This continued even after the defeat of sirajuddaula. The English officers of the east india company and English merchants maintained harem in the style of the nawabs. In the English harem there were Armenian, Portuguese, Bengali and also women from different parts of India.

Normally the Bengal nawabs married more than two or three wives. The senior most wife commanded the greatest respect and influence. The whole management of the harem was under the direct command of the nawab. The nawab visited a particular wife on a particular day. The kaneezes arranged for all kinds of comforts for him. Only the favourite wife accompanied the nawab when he would go out. The rest of the wives were left behind under the care of the eunuchs. These ladies in the nawab's harem wore the most expensive clothes, ate rich food and enjoyed all worldly pleasures. They were often very jealous of each other for gaining favours of the nawab. Eunuchs and purchased Bengali slave girls were appointed to guard each wife to ensure that she was seen by no other man except the nawab. The other ladies of the nobility (wives of amirs) also led a luxurious life.

Each wife of a Bengal nawab lived in a separate apartment of the palace. They were given monthly allowances. They had many slaves and maids to serve them. Their grandour varied according to their influence upon the nawab. Massive walls, with tanks and gardens inside surrounded the apartments of these Begums. Following the Mughal tradition the Bengal nawabs kept concubines. These concubines did their best to attract and please the nawab and encouraged him to use opium and intoxicating drugs and also played musical instruments. These concubines sometimes took the place of the real begums who, naturally, felt jealous of them. Each concubine had her own apartment.

There were however exceptions among the Bengal nawabs who conducted the harem administration in a different way. alivardi khan was a man of piety and contemporary Europeans have paid eloquent tribute to the qualities of this remarkable man. He abstained from wine and women, conferring his loyalty to his only wife. Alivardi never entered the zenana without sending notice. Wives and daughters of fallen rebel chiefs found asylum in the harem of Alivardi. They were treated with kindness and assigned decent accommodation in the inner apartments of the harem. Whenever he received any fruit or any special gift he sent those to his consort and other ladies of the harem. After his evening and night prayers Alivardi ate some fruits and sweets in company of his begum and ladies of the zenana. At this time he drank a cup of water cooled with saltpetre or with ice.

Some ladies of the Bengal nawab's harem played important roles in contemporary society and politics. They are ghaseti begum, lutfunnisa begum and munni begum. [Shahryar ZR Iqbal]

Bibliography Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akbari, Vol. I (Translated by H Blochman), 2nd ed, Calcutta, 1939; Jadunath Sarker, The History of Bengal, Vol. 11, Dhaka, 1948; Shahryar Iqbal, Mughol Shomaj O Rajnitite Nari (in Bangla), Dhaka, 1995.

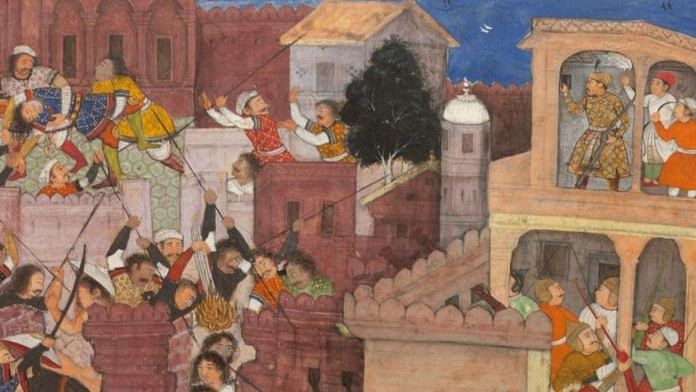

The Akbarnama, which translates to Book of Akbar, the official chronicle of the reign of Akbar, the third Mughal Emperor (r. 1556–1605), commissioned by Akbar himself by his court historian and biographer, Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, called one of the 'nine jewels in Akbar's court' by Mughal writers. It was written in Persian, which is the literary language of the Mughals, and includes vivid and detailed descriptions of his life and times.[1] It followed the Baburnama, the more personal memoir by his grandfather, Babur, founder of the dynasty. Like that, it was produced in the form of lavishly illustrated manuscripts.

The work was commissioned by Akbar, and written by Abul Fazl, one of the Nine Jewels (Hindi: Navaratnas) of Akbar's royal court. It is stated that the book took seven years to be completed. The original manuscripts contained many miniature paintings supporting the texts, thought to have been illustrated between c. 1592 and 1594 by at least forty-nine different artists from Akbar's studio,[2] representing the best of the Mughal school of painting, and masters of the imperial workshop, including Basawan, whose use of portraiture in its illustrations was an innovation in Indian art.[3]

After Akbar's death in 1605, the manuscript remained in the library of his son, Jahangir (r. 1605-1627) and later Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658). Today, the illustrated manuscript of Akbarnma, with 116 miniature paintings, is at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was bought by the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) in 1896 from Mrs Frances Clarke, acquired by her husband upon his retirement from serving as Commissioner of Oudh (1858–1862). Soon after, the paintings and illuminated frontispiece were removed from the volume to be mounted and framed for display.[4]

Volumes I and II[edit]

The first volume of Akbarnama deals with the birth of Akbar, the history of Timur's family and the reigns of Babur and Humayun and the Suri sultans of Delhi. Volume one of Akbarnama encompasses Akbar's birth and his upbringings. According to the Abul Fazl Humayun, the second Mughal emperor and Akbar's father is praying to the Ka'ba, an Islamic holy place, for a successor to the Mughal empire. After this prayer, Maryam Makani showcases different signs that she is pregnant with Akbar such as having a shining forehead that others believe to be a mirror on her face or the warmth and joy that enters her bosom when a light shines on her. Miryam believes the light to be God's Light blessing her and her unborn child. Nine months later while Humayuan is away, Maryam gives birth to Akbar under what is considered an auspicious star and there is great celebration.[5]

The second volume describes the detailed history of the reign of Akbar till 1602 and records the events during Akbar's reign. It also deals with how Bairam Khan and Akbar won the battle of Panipat against Hemu, an Indian warrior.

Volume III: The Ain-i-Akbari[edit]

Akbarnama In Bengali Pdf

The third volume, called the Ā’īn-i-Akbarī, describes the administrative system of the Empire as well as containing the famous 'Account of the Hindu Sciences'. It also deals with Akbar's household, army, the revenues and the geography of the empire. It also produces rich details about the traditions and culture of the people living in India. It is famous for its rich statistical details about things as diverse as crop yields, prices, wages and revenues. Here Abu'l Fazl's ambition, in his own words, is: 'It has long been the ambitious desire of my heart to pass in review to some extent, the general conditions of this vast country, and to record the opinions professed by the majority of the learned among the Hindus. I know not whether the love of my native land has been the attracting influence or exactness of historical research and genuine truthfulness of narrative..' (Āin-i-Akbarī, translated by Heinrich Blochmann and Colonel Henry Sullivan Jarrett, Volume III, pp 7). In this section, he expounds the major beliefs of the six major Hindu philosophical schools of thought, and those of the Jains, Buddhists, and Nāstikas. He also gives several Indian accounts of geography, cosmography, and some tidbits on Indian aesthetic thought. Most of this information is derived from Sanskrit texts and knowledge systems. Abu'l Fazl admits that he did not know Sanskrit and it is thought that he accessed this information through intermediaries, likely Jains who were favoured at Akbar's court.

Akbarnama In Bengali Pdf Free

In his description of Hinduism, Abu’l Fazl tries to relate everything back to something that the Muslims could understand. Many of the orthodox Muslims thought that the Hindus were guilty of two of the greatest sins, polytheism and idolatry.[6]

On the topic of idolatry, Abu’l Fazl says that the symbols and images that the Hindus carry are not idols but merely are there to keep their minds from wandering. He writes that only serving and worshipping God is required.[7]

Abul Fazl also describes the Caste system to his readers. He writes the name, rank, and duties of each caste. He then goes on to describe the sixteen subclasses which come from intermarriage among the main four.[8]

Abu’l Fazl next writes about Karma about which he writes, “This is a system of knowledge of an amazing and extraordinary character, in which the learned of Hindustan concur without dissenting opinion.”[8] He places the actions and what event they bring about in the next life into four different kinds. First, he writes many of the different ways in which a person from one class can be born into a different class in the next life and some of the ways in which a change in gender can be brought about. He classifies the second kind as the different diseases and sicknesses one suffers from. The third kind is actions which cause a woman to be barren or the death of a child. And the fourth kind deals with money and generosity, or lack thereof.[9]

The Ain-i-Akbari is currently housed in the Hazarduari Palace, in West Bengal.

The Akbarnama of Faizi Sirhindi[edit]

The Akbarnama of Shaikh Illahdad Faiz Sirhindi is another contemporary biography of the Mughal emperor Akbar. This work is mostly not original and basically a compilation from the Tabaqat-i-Akbari of Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad and the more famous Akbarnama of Abu´l Fazl. The only original elements in this work are a few verses and some interesting stories. Very little is known about the writer of this Akbarnama. His father Mulla Ali Sher Sirhindi was a scholar and Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad, the writer of the Tabaqat-i-Akbari was his student. He lived in Sirhind sarkar of DelhiSubah and held a madad-i-ma´ash (a land granted by the state for maintenance) village there. He accompanied his employer and patron Shaikh Farid Bokhari (who held the post of the Bakhshi-ul-Mulk) on his various services. His most important work is a dictionary, the Madar-ul-Afazil, completed in 1592. Canon imageclass d1150 scan software. He started writing this Akbarnama at the age of 36 years. His work also ends in 1602 like the one of Abu´l Fazl. This work provides us with some additional information regarding the services rendered by Shaikh Farid Bokhari. It also provides valuable information regarding the siege and capture of Asirgarh.[10]

Translations[edit]

- Beveridge Henry. (tr.) (1902–39, Reprint 2010). The Akbarnama of Abu-L-Fazl in three volumes.

- The History of Akbar, Volume 1 (the Akbarnama), edited and translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, Murty Classical Library of India, Harvard University Press (January 2015), hardcover, 656 pages, ISBN9780674427754

References[edit]

- ^Illustration from the Akbarnama: History of AkbarArchived 2009-09-19 at the Wayback MachineArt Institute of Chicago

- ^'Akbar's mother travels by boat to Agra'. V & A Museum.

- ^Illustration from the Akbarnama: History of AkbarArchived 2009-09-19 at the Wayback MachineArt Institute of Chicago

- ^'Conservation and Mounting of Leaves from the Akbarnama'. Conservation Journal (24). July 1997. Archived from the original on 2008-03-24.

- ^https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.30000125233498. 'The Akbarnama of Abu-l-Fazl' Translation from Persian by H. Beveridge.

- ^Andrea; Overfield: “A Muslim’s Description of Hindu Beliefs and Practices,” “The Human Record,” page 61.

- ^Fazl, A: “Akbarnama,” Andrea; Overfield: “The Human Record,” page 62.

- ^ abFazl, A: “Akbarnama,” Andrea; Overfield: “The Human Record,” page 63.

- ^Fazl, A: “Akbarnama,” Andrea; Overfield: “The Human Record,” page 63-64.

- ^Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN81-7276-407-1, p.7

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). 'Abul Fazl'. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Akbarnama In Bengali

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Akbarnama. |

- Akabrnama Online search through collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Fazl, Abu'l (1877). Akbarnamah (Persian). Asiatic Society, Calcutta.Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. I-III